A guest blog for the Bar Council by First Tier Tribunal Judge Ifey Munonyedi reflecting on key Black figures in British history during Black History Month.

British history belongs to us all and we all need to understand the whole of our history and the part that each section of society has played.

I studied British history in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I was the only Black student in the History Department and the Arts Faculty. In my course of study, there was a deafening silence when it came to the presence of historical Black Britons.

I have been on a fascinating personal journey trying to discover the presence and contribution of Black Britons to our history. I have discovered so much and would like to share just a little with you in celebration of Black History Month.

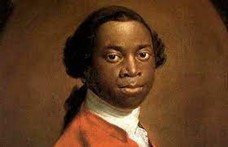

OLAUDAH EQUIANO (c. 1740-1797)

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah claimed to be an Igbo from Eastern Nigeria, who with his sister, at the age of about 10 years old, was kidnapped by African slave catchers. (There are historians who believe that he was born not in Africa but as a slave in South Carolina).

He was transported to Barbados and sold to Michael Pascal, a British naval officer and renamed Gustavus Vassa. He travelled with Pascal aboard British naval ships to the West Indies, North America, Central America, Britain, and the Mediterranean. He took part in the Seven Years War, 1756-1763, fighting for Britain. During this time Olaudah learnt to read and write.

Despite a promise of freedom from Pascal, this did not materialise, and in 1762 he was sold to a merchant Robert King. Olaudah worked on King’s ship in the West Indies and was allowed to engage in his own private business. He was able to raise the £40 demanded from King to buy his freedom.

In the 1760s he ended up in London and worked as a hairdresser, living amongst the small Black population of a few thousand people. He slowly began to develop a reputation as a spokesman for the Black community and as an abolitionist.

In 1767 he tried to stop the illegal transportation of a free man, John Annis, to St Kitts by his former slave master. He was appointed Commissary of Provisions and Stores to oversee the resettlement of Black people to Sierra Leone. During this time, he witnessed the ill treatment of Black people and corruption. Having reported the matter, he was relieved of his duties.

Olaudah became a leading light in ‘the Sons of Africa’, a group of Black men who campaigned for the ending of slavery. He lobbied Parliament and joined forces with White allies such as Thomas Clarkson. He worked closely with Granville Sharpe, the Chairman of the committee to abolish the slave trade.

In 1783, Olaudah brought to Sharpe’s attention the scandal of the ‘Zong,’ the Liverpool slave ship where 132 sick enslaved people were thrown overboard so that the owners could make an insurance claim against their loss.

Olaudah was a capable and energetic publicist, fluent writer and speaker. He wrote many articles for London newspapers. Between 1789 and 1793 he went on speaking tours to Birmingham, Manchester, Nottingham, Sheffield, Cambridge, Durham, Stockton, Hull, Bath, Devizes, and London. He toured Ireland for eight months as well as Scotland.

In 1789, he published his autobiography, ‘Interesting Narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African,’ through which he detailed the horrors of slavery. Olaudah published the book himself and personally chose the bookshops where his book should be sold. A chosen bookshop belonged to a Mr Davis, opposite Gray’s Inn.

During his lifetime, eight editions of his book were published; it was a bestseller read by many, including the Prince of Wales. He was the first Black person to have a book published in Britain.

When the anti-slavery bill was going through Parliament, he was frequently consulted by politicians. During this time he met the Prime Minister and the Speaker of the House of Commons. Sadly, he did not see the abolition of slavery by the time of his death on 31 March 1797.

As one of the most influential people in the fight for abolition, and a recognised spokesman for the Black community, it is fitting that he is remembered during Black History Month.

IGNATIUS SANCHO (1729-1780)

Ignatius Sancho

Ignatius Sancho’s parents were captured and taken in a slave ship to the Spanish colony of Granada, where he was born in 1729.

His father took his own life rather than be subjected to enslavement. His mother died when he was two years old at Cartin Colombia.

In 1731, he was given by his slave owner to three sisters who lived in Greenwich. They renamed him Sancho. They decided not to educate him. However, their neighbour, the Duke of Montague, took an interest in Sancho. He wanted to discover whether a Black person could be educated. Books were made available to Sancho which gave him the opportunity to blossom into a cultured and educated young man. Frustrated by the limitations set upon him by the sisters, in 1749 he ran away and moved into the household of the Duchess of Montague.

Sancho was musically talented and composed music for the popular dances of the time, such as the minuet and country dance, as well as songs for the piano, flute, violin and harpsichord. His music was published and therefore accessible to all. His music was played everywhere, from the drawing rooms and salons of the aristocracy and upper classes to the pubs and parks frequented by the several thousand strong Black population of enslaved and free people. Sancho was one of the most famous and well-known composers of his time.

In 1768 he was painted by Thomas Gainsborough. He was considered a formidable writer and poet moving in literary circles. He counted David Garrick and Charles James Fox as colleagues. Sancho collaborated with others to fight slavery and recognised the need for allies. His status and position gave him access to influential people. The most popular author at this time was Lawrence Sterne, who was also a friend. Sancho asked Sterne to use his platform as a writer to oppose slavery. Sterne did so in ‘The life and opinion of Tristram Shandy’, where – in response to Sancho’s request – he includes the depiction of the life of an enslaved woman.

Sancho married a woman from the West Indies and they had seven children. With his savings and monies given to him by the Montagues, he bought a grocery shop in Charles Street Mayfair.

He died in 1780. In 1782 his letters to friends were published in ‘Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho, an African’ which became a bestseller.

Ignatius Sancho was the first Black person to:

have his music published

have his letters published

have the right to vote in a British election

be a patron of White artists and writers

have had a published obituary

You can find a plaque at Greenwich Park in his honour.

MARY PRINCE (c.1788-1833)

No photographs of Mary Prince exist. This is Souria Adèle, who has played Prince in a modern theatre production.

Mary Prince was born in Bermuda in 1787/1788 to enslaved parents owned by Charles Minors. She was sold to George Darell who gave her as a playmate to his granddaughter. At the age of 12 she was sold at auction for £57 to Captain Ingham who treated her cruelly. Mary ran away to her mother but was returned by her father to her owner.

A few years later she was sent to the Grand Turks Island to work in the salt industry. She was bought by Richard Darell for £100 and continued working in the salt industry for a further 10 years. Mary returned to Bermuda with her owner and was rented out. Her wages were given to her owner.

She was rented out to John Woods in Antigua who later bought her for £100. She worked for him for 13 years in Antigua.

Mary joined the Moravian Congregation where she was taught to read and write. On Christmas Day 1826 she married Daniel James, a free man, without the permission of her slave master.

In 1828, she was taken to London by Woods. Very soon after her arrival in London she left the Woods’ home, with a wish to return to her husband in Antigua. She found work and in November made contact with Thomas Pringle, the leader of the Anti-Slavery Society.

George Stephen, the abolitionist lawyer tried to negotiate her freedom with John Woods, but he refused. On 24 June 1829, Mary petitioned Parliament to allow her to return to the West Indies. The petition was unsuccessful.

Mary wanted to tell people about the horrors of slavery and decided to write a book. She recounted her story to Susanna Strickland who wrote everything that Mary told her. Pringle edited and financed the publication. Mary’s first-hand experience of being enslaved, ‘The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, related by herself’ was published in 1831.

Mary’s book was popular, particularly amongst female anti-slavery campaigners, and played a vital role in the fight against slavery.

The Slavery Abolition Act received the Royal Assent on 28 August 1833.

Mary returned to her husband very soon after.

In 2012 Mary was recognised as a National Hero in Bermuda and from 2020 the 2nd of August has been known as Mary Prince Day in Bermuda.

Mary Prince was the first Black woman to publish an autobiography and to petition Parliament.

Sources

‘The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano’ by Olaudah Equiano

‘Voices from Slavery’ by Chigor Chike

‘Mary’ by Margot Maddison MacFadyen

‘Black and British’ by Professor David Olusoga